Why mimicking a device is becoming almost impossible

MAY 24, 2021 | FINGERPRINTS

If you've seen Quentin Tarantino's film Inglourious Basterds, you probably remember the bar scene where a British spy undercover as a Nazi officer drops his mask through an unconscious gesture.

Although he wears a Nazi uniform and speaks German well, he gives himself by a minor detail: his fingers. When ordering three more pints, instead of using his thumb, index and middle fingers (as Germans do), he uses his ring, middle and index finger. Another officer at the table immediately recognizes this subtle detail as unmistakably Anglophone.

The same goes for any of us working online. Dropping your guard and giving out your identity is easy if you overlook some minor-looking vital points. In this article, we will take a journey into the world of device detection, and show why and how mimicking a device is getting almost impossible.

The same goes for any of us working online. Dropping your guard and giving out your identity is easy if you overlook some minor-looking vital points. In this article, we will take a journey into the world of device detection, and show why and how mimicking a device is getting almost impossible.

Before diving in, let's have a quick look at why systems try to detect devices – which is also the answer to why people try to detect or emulate devices.

Why do systems try to detect devices?

In the early days of browsers and throughout the subsequent 'browser wars', the myriad of browser vendors meant developers needed to understand which client developed by which vendor was connecting to their websites, and they started customizing and optimizing the response according to the browser detected. In this sense, it was a technical necessity.

Dropping your guard and giving out your identity is easy if you overlook some minor-looking vital points.

Our old friend the User-Agent string is a survival from these days – but nowadays detection and prevention techniques are both now much more advanced.

On the detection side, most sites adopt detection mechanisms to help serve their clients. For example, Netflix supports hundreds of different video formats in various resolutions for each device, from mobile devices to smart TVs. Without device detection, how would that be possible?

Likewise, think about companies who offer fully capable products to laptop and desktop devices, they offer only a limited version to mobile users.

But...why do individuals and bots try to mimic devices?

The questions we asked so far brought us here, and the answer is the question. People or bots who want to get more elements specific to certain devices, or who want to break out of so-called 'device ghettoes' (eg they don't want to have restricted possibilities due to being a mobile device). Likewise, some threat actors want to take advantage of the fact that some security measures are not as tight for some devices.

Who can stop people from utilizing device spoofing if a website cannot show captcha to mobile devices even if some rate limits are exceeded, or if a company offers specific discounts or products only to some types of devices?

An arms race: detection and prevention

This brings us to the present day: a metaphorical 'arms race' to come out top between those trying to detect devices and those trying to prevent that detection. While this has led to greater investment in advanced tech like machine learning or AI, there are some other methods that have surprisingly not drawn much attention, like Google's device classification method, Picasso. We'll look at it in detail at this shortly, but first, let's not forget those tiny details that can give you away in a second.

Why does device spoofing not always work?

From modifying User-Agent strings to employing more advanced techniques, device spoofing is possible in different ways – but this also means different ways of discovery.

Are you on mobile? Really?

Many people think that spoofing a device is as easy as changing the User-Agent string: we say to them, "claiming is cheap; show your proof!"

For example, most spoofing attempts claiming that the device is mobile give the game away immediately. They forget to mimic device-specific features, such as answering questions about touch support negatively.

Can you imagine a smartphone that does not have touch support?

Try it with your solution.

1var touch_capable = ( 'ontouchstart' in window ) ||2 ( navigator.maxTouchPoints > 0 ) ||3 ( navigator.msMaxTouchPoints > 0 );45if(touch_capable) {6 alert("Supported");7} else {8 alert("Not Supported");9}10

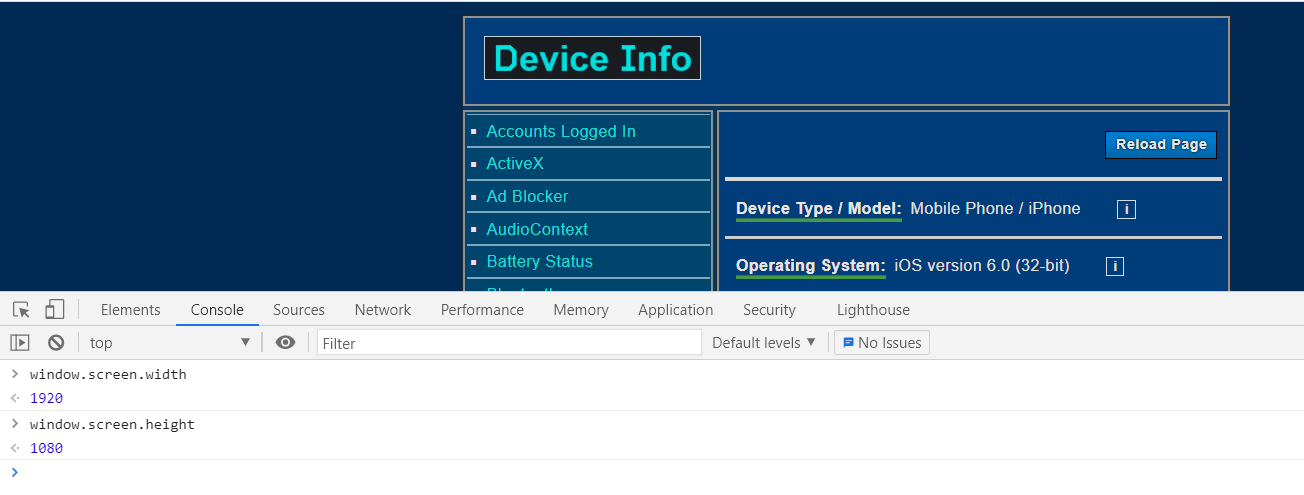

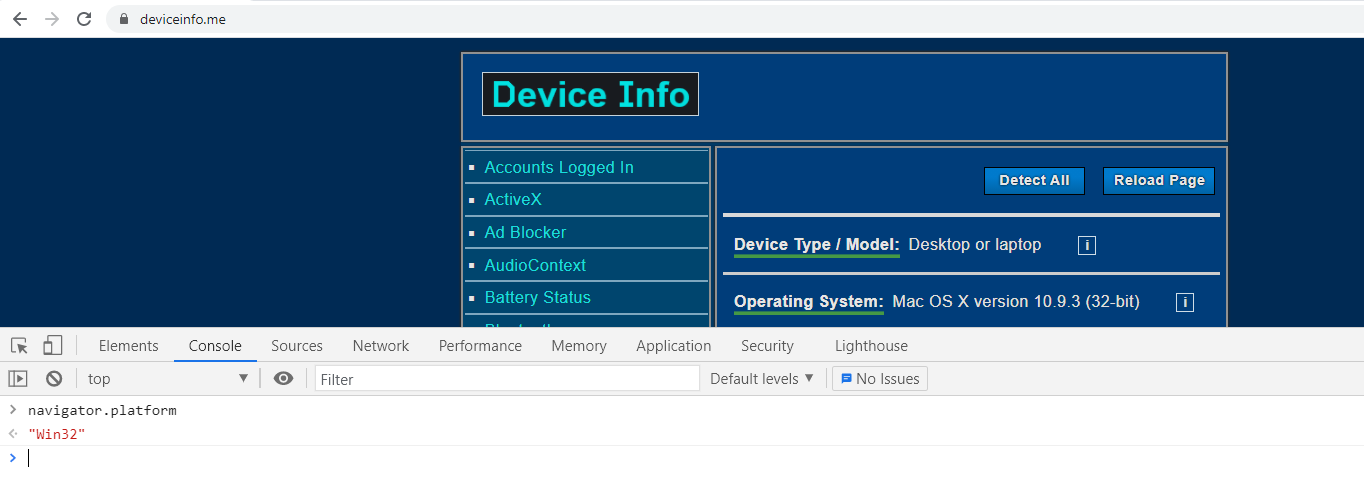

As we said, device-specific features and information are essential. If you claim that your device is Apple iPhone 6, you have to know device-specific details, at least the screen size of the iPhone 6.

Have you ever seen an iPhone 6 that has a screen resolution of 1920x1080? We have not and nor have detection systems!

Another example: no-one would find it odd that you have a MacBook, if you pass the navigator.platform test successfully:

Another example: no-one would find it odd that you have a MacBook, if you pass the navigator.platform test successfully:

However, you cannot claim that you're using Max OS X and Windows simultaneously!

However, you cannot claim that you're using Max OS X and Windows simultaneously!

There are more anomalies overlooked while spoofing a device. If you have ever used a mobile browser (of course you have), you know you cannot resize the browser window. It's always opened, maximized, covering the whole screen. This means for a detection system that the X and Y values of the window should always be 0, and if not..

Examples regarding device-specific attributes can go on, but it's time to smile a little.

Emojis: are your feelings betraying you?

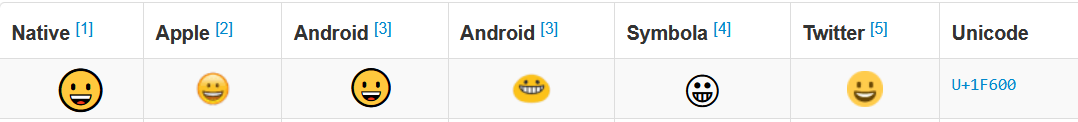

Did you realize that emojis, while typed the same way, are visualized differently in different devices?

For example, here is a smile emoji, using : and ) for it, and your system converts it to a sweet picture. 🙂

Look how different this sweet symbol is in each system and device. Let’s say your client claims that it runs on Android OS. A detection system can obtain the hash value of the emoji and compare it with one obtained from a genuine Android system. If the result is not the same, it highlights that you are spoofing your device. It is real magic! Just use a U+1F600 and while producing visualization, add a value that defines you amongst others.

Let’s say your client claims that it runs on Android OS. A detection system can obtain the hash value of the emoji and compare it with one obtained from a genuine Android system. If the result is not the same, it highlights that you are spoofing your device. It is real magic! Just use a U+1F600 and while producing visualization, add a value that defines you amongst others.

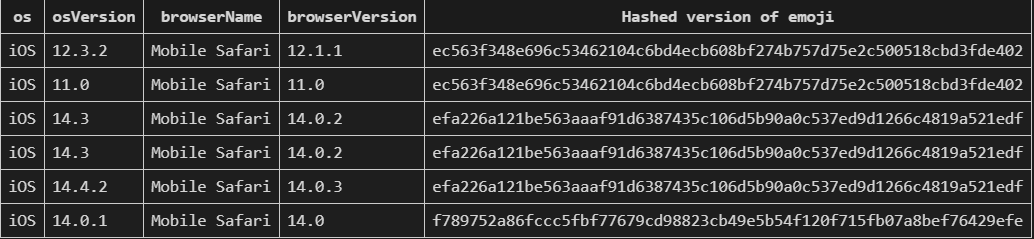

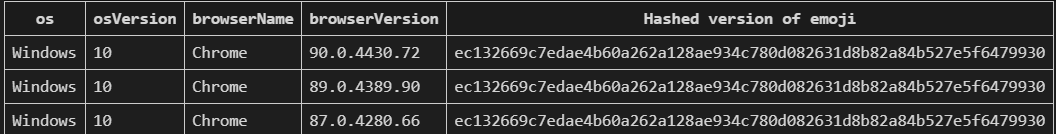

Here is hashed version of U+1F600 smile emoji from different devices. Here sha256 hashed out of same emoji obtained from different version of Google Chrome on Windows 10 OS.

Here sha256 hashed out of same emoji obtained from different version of Google Chrome on Windows 10 OS.

Do your fonts match?

Do your fonts match?

Each system comes with some preinstalled fonts, with certain specific ones used as default. For example, while iOS 13 Academy has Engraved LET Plain:1.0 font preinstalled, it doesn't have Al Bayan Bold. However, macOS Catalina does!

Likewise, while Tahoma was the default font in Windows XP, since Vista, it's been Segoe UI. Microsoft's latest font list for Windows 10 comes with a note:

"Please note: Not all of the Desktop fonts will be in non-desktop editions of Windows 10 such as Xbox, HoloLens, SurfaceHub, etc."

So detection systems that probe fonts can decide immediately you're not a normal Windows 10 if they don't see fonts listed Microsoft's page.

PUF!!! (Physically Unclonable Functions)

Up to this point, we examined some issues which give spoofing away, but are not to difficult to find a workaround for. By overriding the browser and shipping font, emoji and binary attributes, it's a problem that you can tackle, albeit requiring a lot of effort and cost to you.

Google Picasso understands the browser's device classification by doing some rendering operations heavily dependent on the OS and graphic hardware.

However, there's another side to the coin.

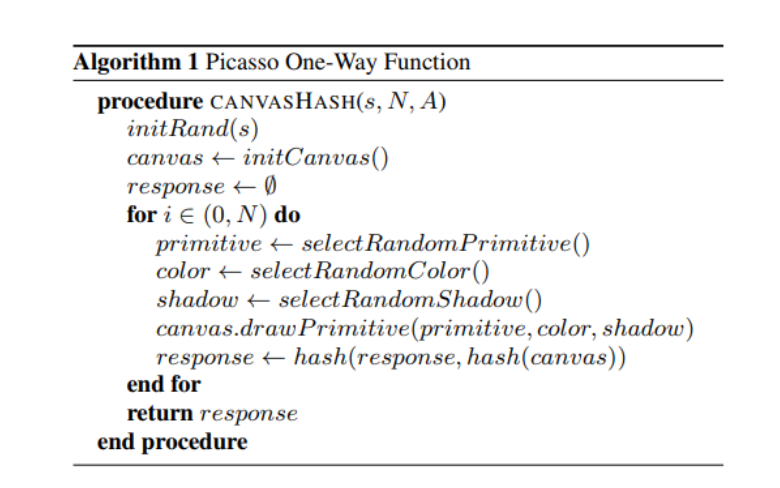

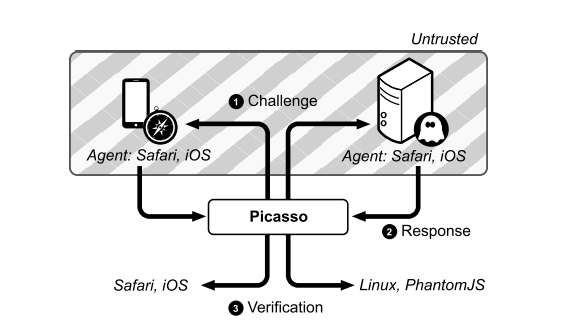

In 2006, Elie Bursztein from the Google anti-abuse team shared his work called Picasso publicly to detail how Google fights device spoofing attempts in Google Play.

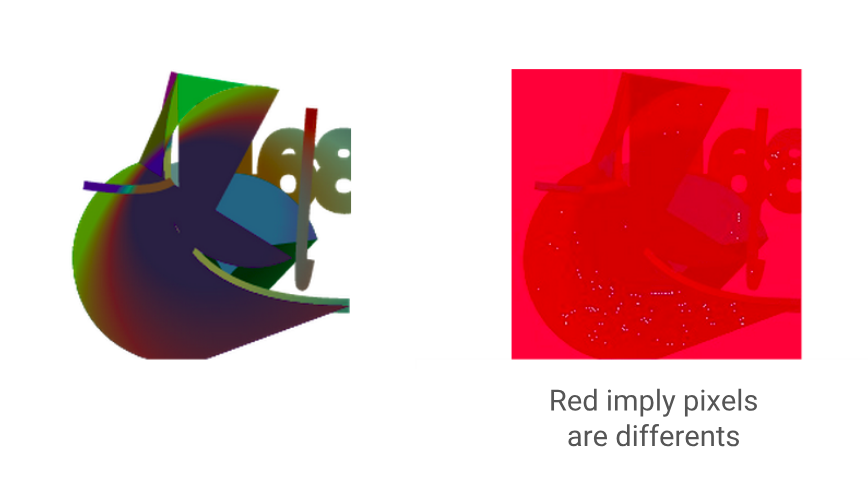

Picasso is designed to understand the browser’s device classification by doing some rendering operations heavily dependent on the browser’s operating system and graphic hardware. By using a seed, Picasso creates geometric symbols on a canvas randomly in each round. Values like seed, round, width, and height are ingredients of Picasso's operation. In a result, Picasso can get a graphical output produced by the client’s unclonable features like operating system and graphic hardware. The spoofer cannot prevent this unless s/he has the same setup in hand.

This system does not mean anything unless a database has precalculated values obtained by using genuine devices. This database is used as a true reference later on.

This system does not mean anything unless a database has precalculated values obtained by using genuine devices. This database is used as a true reference later on.

We have to note some important points of Picasso's work here. For example, it produces graphical work by using HTML canvas. Folks tend to think that canvas is used to increase fingerprint entropy to attain uniqueness. As Multilogin engineers proved years ago, instead of promising unique fingerprints, canvas hash would be identical in setups with the same ingredients as hardware. In 2006, Google guys started to use this feature of canvas fingerprint to classify devices for understanding device spoofing attempts.

We have to note some important points of Picasso's work here. For example, it produces graphical work by using HTML canvas. Folks tend to think that canvas is used to increase fingerprint entropy to attain uniqueness. As Multilogin engineers proved years ago, instead of promising unique fingerprints, canvas hash would be identical in setups with the same ingredients as hardware. In 2006, Google guys started to use this feature of canvas fingerprint to classify devices for understanding device spoofing attempts.

Although this is considerably old work (2006), it has been adapted by Cloudflare. When we think about how significant their market share is, Picasso would stand as an unpreventable mechanism for device spoofing attempts.

Although this is considerably old work (2006), it has been adapted by Cloudflare. When we think about how significant their market share is, Picasso would stand as an unpreventable mechanism for device spoofing attempts.

As long as opposite sides have a database consisting of precalculated hashes obtained by genuine devices, it seems difficult to escape from Picasso for device and operating system spoofing attempts. Don't you think Google and Cloudflare have enough datasets to check device authenticity?

Conclusion: "Either seem as you are or be as you seem"

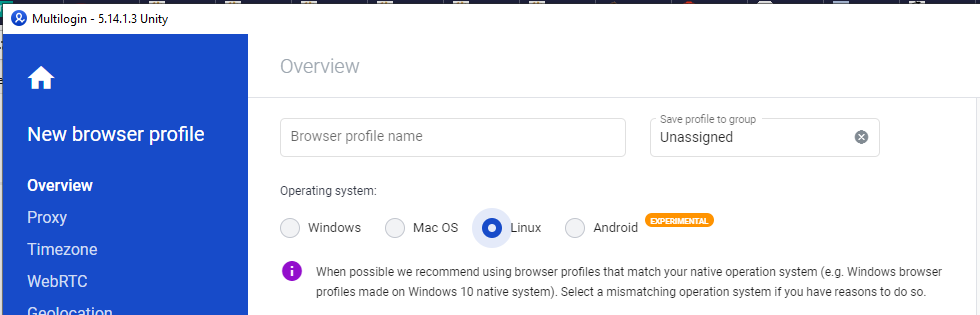

This quote from poet Rumi could have be tailor-made for our situation. For a long time, we have advised our users when creating browser profiles in Multilogin to be sure to select the correct operating system that the browser profiles work on. Although Multilogin takes some steps to prevent detection systems by shipping fonts with profiles, deliver authentic canvas result default, etc.; the best is to stay authentic as it could be. Leaving operating systems does not mean anything to detection systems; however, detecting a mismatch between supposed settings means a lot!

Although Multilogin takes some steps to prevent detection systems by shipping fonts with profiles, deliver authentic canvas result default, etc.; the best is to stay authentic as it could be. Leaving operating systems does not mean anything to detection systems; however, detecting a mismatch between supposed settings means a lot!

The key rule is blending in the crowd for not being the person pointed to by finger. From a device spoofing perspective, as Rumi says, we would suggest: Seem as you are or be as you seem!